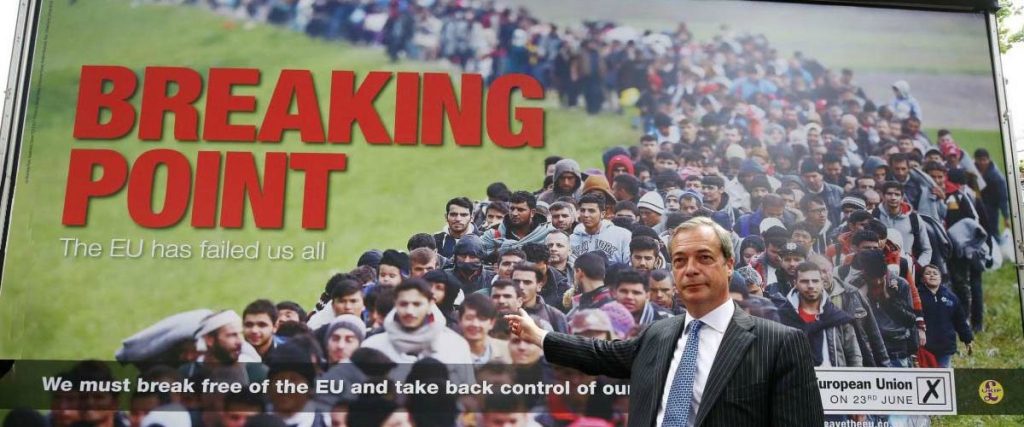

There are many diverse groups celebrating Brexit: the little Englanders who are not very keen on migrants and/or are nostalgic for all things English; those who have been disaffected and disenfranchised by 30 years of British neoliberalism (implemented by Tory and Labour governments); the old; the fascists; the ‘libertarians’ seeking an opportunity for further deregulation; and finally, probably to the astonishment of the broader part of the left, a handful of tiny left factions, which seem unable to deal with the changing coordinates of political reality. This was the key in the Brexit campaign’s success: cutting across traditional class divides, transgressing the left-right political spectrum, offering a platform where all grievances can be projected – the EU as the entity blocking us from controlling ‘our’ society, from contacting ‘our’ politics, from having ‘sovereignty’.

This is not unusual as a political operation, but it has different content, possibilities and consequences depending on whether it is framed as a ‘left’ project or as a ‘right’ one. In this sense the British referendum was the opposite of the Greek one a year ago. Greece had elected a left government that was under extreme pressure to accept a neoliberal agenda and further austerity. Despite the imposed capital controls, the Greek people voted overwhelmingly (62 per cent) against austerity only to see their mandate and their government cast aside by a powerful neoliberal block dominating the EU and the eurozone.

Lesser of two evils

Greece has been the most visible and egregious example of what the EU has become. The choice to remain in the EU, the lesser of two evils, did not divert from the realisation that the EU will either change or perish. The beginning of the end for the European project was known even to the most un-insightful commentator, since Germany’s finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble announced the possibility of a ‘two-speed’ EU a year ago (a plan more plausible after Brexit) and when the meetings of the Visegrad group against the refugee influx brought them head to head with other European countries. It is also a real threat in every other instance that nationalism and xenophobia win ground around Europe.

The question has always been how to keep unity, solidarity and cooperation, while blocking the neoliberal agenda. For many of us the answer is by building transnational movements, to support left-wing parties in order to win national elections, changing the balance of powers within the EU and enabling the formation of a new anti-neoliberal power block. Transnational cooperation is the key, rather than the dissolution of the EU and a return to parochial nationalist politics. With that in mind, the defeat of the progressive forces at the Spanish national elections (see page 22) has been a great disappointment.

In the case of Britain, it is true that a Remain vote seemed to have little to offer in terms of the realisation of a left-wing strategy. Britain in the EU had been one of the main powers driving neoliberalism, supporting financialisation, deregulation, TTIP and all things that the left despises. A Brexit, however, had plenty to offer as a psycho-ideological boost to European nationalism and the far right (see congratulatory messages from the Greek neo-Nazi Golden Dawn and the French far-right Marie Le Pen). Any left celebration of this displacement can be nothing more than a cover up of delusional narrow mindedness, despair, lack of any strategic consideration or all the above.

Political contempt

This is why my political contempt is reserved for two groups that showed an astonishing lack of political judgement after the referendum: the parliamentary Labour party (for losing touch with those it was supposed to represent a long time ago and for staging an attack on Corbyn) and the pro-Brexit left.

The latter, despite their insignificant influence on the referendum campaign and their continuous attempts to red-wash or sanitise the outcome, are responsible for much more than an epic lack of judgement. Their inability to analyse the contemporary political situation and develop an appropriate strategy have led them to re-enacting events from the dustbin of history. Their attitude is a reminder of the 1930s, when Hitler was ascending to power but for the German Communist Party this was a signal that the time of the left was arriving. We may not be in that situation (yet) but remaining totally unfazed as the congratulatory messages from European fascists pour in and the anti-migrant attacks escalate is an indication that one’s relationship with reality has been seriously compromised.

In an attempt to capitalise on what is clearly a far-right victory, the pro-Brexit left tries to present it as a victory of the ‘working class’. In this instance ‘the working class’ is composed of white, male, old and English Brexit supporters. The young, the Scottish, the Irish and, above all, the two million EU nationals working in Britain cannot be part of the working class a la ‘Lexit’. This is why the ‘Lexit’ side did not provide EU nationals with any support to help them have a vote in this referendum. Better to silence them than spoil the Brexit/Lexit result. Now that the xenophobic, anti-migrant wave has been unleashed, they offer their ‘solidarity’ (sic).

Sanitising domestic neoliberalism

Because the Brexit terrain was set by the right and far right, the left Brexit had to move a step further to sanitise domestic neoliberalism. No references to Thatcherism and the impact it had on the welfare state and labour rights. Instead, and against almost all union advice, a praise of the superiority of the (almost socialist, in their left-Brexit account) rights we enjoy in Britain. How anyone – especially those who lost employment security a long time ago and are familiar with the precarious, part-time, zero hour-contract principles of the UK labour market – can misrecognise this position as being in the interest of the ‘working class’ is beyond me. Not only because it reveals a stupendous ignorance of employment law but above all because it conceals the fact that the attack on labour rights we witness across the EU is a continuation of the project that started here and was exported to the continent.

Similarly, the pro-Brexit left suddenly became the most vocal cheerleaders of liberal democracy during the campaign. The mantra ‘the EU is undemocratic’ was repeated time and again without any further explanation. Yes, the EU is undemocratic – and the same can be said for national institutions too. To imply that a country with a ‘first-past-the post’ electoral system, the House of Lords, a hereditary monarchy, the City of London and the Murdoch press is more democratic, and that the British people will be granted a voice post-Brexit, shows how delusional the pro-Brexit left is.

Right-wing narratives

Let me finish with a prediction. The Brexit campaign brought together a number of narratives, none of which signals any progress towards social justice and democracy. A conservative narrative (intolerant of migration, globalisation and change in traditional institutions); a neoliberal narrative (where the most contested issues with TTIP will be implemented via the new trade agreements between, for example, the UK and US); and finally the ‘libertarian’ vision of people who are not bothered about immigration as long as it is about letting in the rich and talented (or those who serve them cheaply).

I suspect the negotiations between the EU and the incoming Tory government over Brexit will be a compromise between these narratives. To counteract the devastation this will bring we have to rely on the movements on the streets, the unions, a hopefully centre-left Labour Party, and the possibility of a national alliance of all progressive forces. I suggest the pro-Brexit left takes some time to reflect on how many of these forces it has alienated.

Marina Prentoulis is a senior lecturer in politics and the media at the University of East Anglia and a spokesperson for the Another Europe is Possible campaign. This article first appeared in Red Pepper magazine. Subscribe here.

12th August 2016